Sometimes, I write film reviews during film festivals. At this year’s Sundance, I wrote about a half-dozen reviews (including highlights such as Eno and War Game). Mind you, in many cases, this isn’t “criticism”—I’m not sure if that’s possible when you have 1-2 hours to evaluate a film quickly in the pressure-cooker intensity of a film festival. And while I do think there are some amazing superhuman experienced critics out there who manage to turn a thoughtful review around in record time, accurately analyzing and assessing a film’s strengths and weaknesses, there are many that don’t. Because of this, too much power lies in these knee-jerk and uninformed reactions, and they can be very dangerous to the fate of a new independent film.

“Too much power lies in these knee-jerk and uninformed reactions, and they can be very dangerous to the fate of a film.”

First reviews are so incredibly important for films launching at a festival like Sundance. We all read them. Distributors, film festival programmers, agents, and audiences all look at these reviews to help us navigate the hundreds of new movies in the festival lineup to make sure that we see the “good” ones. But one prominent pan, or the critical groupthink that bestows quality (or the lack thereof), can be misleading.

We also need to remember the subjective biases of every writer—what they are inclined to like and not. (When I wrote reviews of films clearly not suited to my taste and identity, such as My Old Ass, which was favorable, and Kidnapping, Inc., which was not, I try my best to be objective, but that’s not really possible. I have since found one or two favorable reviews of Kidnapping, Inc., so there are some people that genuinely like it, so who I am to say it’s a mess?)

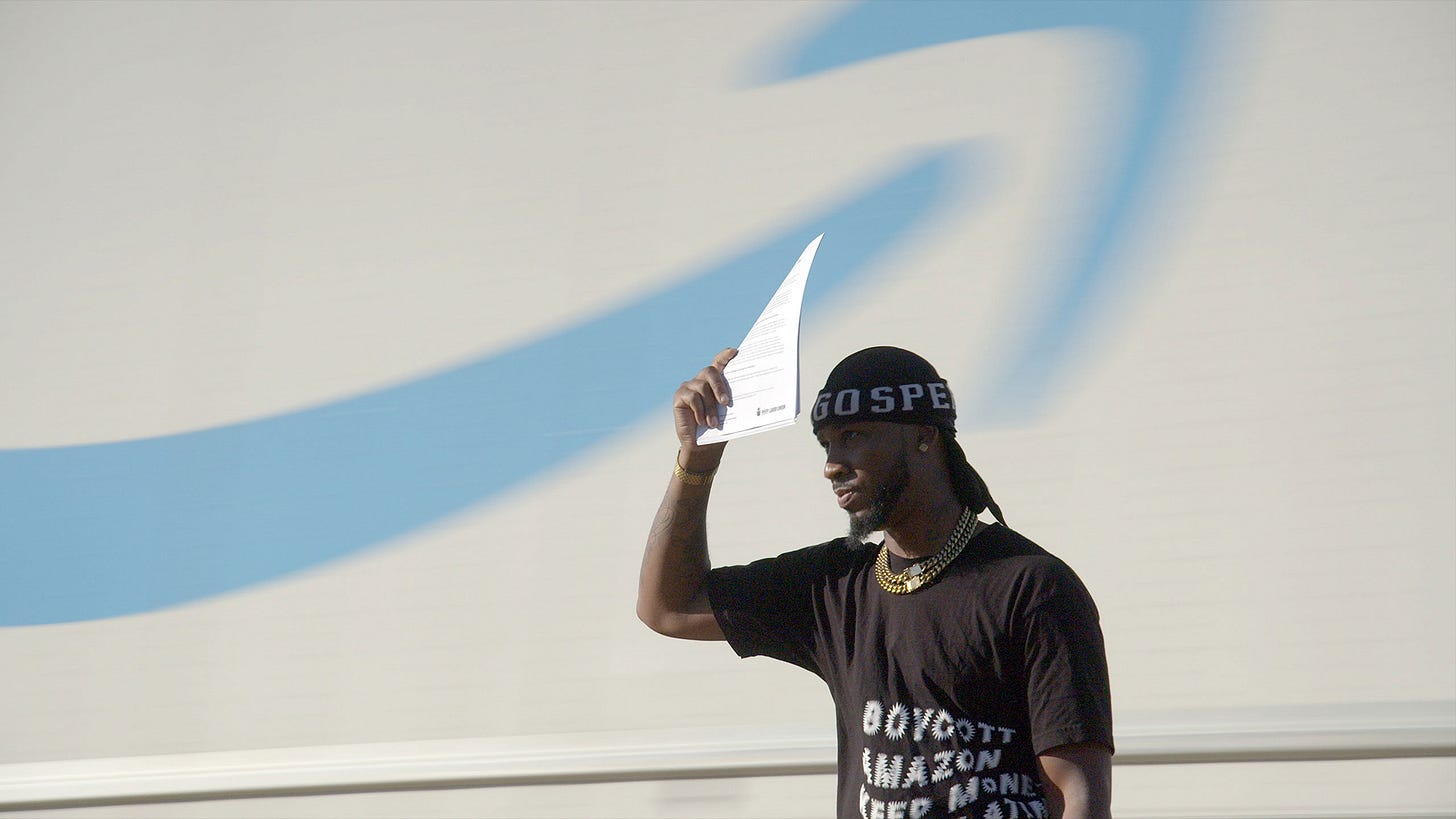

These thoughts began to swirl around in my head on Sunday in Park City after I read a review of Brett Story and Stephen Maing’s Union in one of the trade magazines. Following in the footsteps of direct-cinema masters such as D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, and Albert Mayles, this true-to-form-verite documentary plunges viewers into the experiences of the men and women trying to launch an Amazon Labor Union in New York City.

There are no contextual news reports; no experts or talking heads; no numbers or statistics; no names on screen to help viewers “identify” the subjects (as has become common practice in documentaries). In short, there is no fucking hand-holding. It is pure observational filmmaking. And yet, this one reviewer appeared to be disappointed that the movie was “so narrowly focused” that it failed “to paint a larger portrait of why the fight is necessary” and “there are no real statistics about what the wages at Amazon are and how they are determined.” I wonder what this reviewer would have thought of the Maylses’ 1969 classic Salesman— i.e. Why didn’t the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin give us more information about the earnings of these salesmen, and or why doesn’t it depict their employers as “adversaries”? Should Salesman have provided more “context” about the history of this particular exploited door-to-door salesman workforce? What kind of documentary did the Union reviewer think they were seeing?

Similarly, I’ve seen reviews for Realm of Satan, Scott Cummings’ portrait of Satanists that completely misses the point of the filmmaker’s experimental exercise, criticizing it for not giving more information about Satanism or providing a more conventional entry into the subject’s psychologies rather than the more abstract tableaux he is clearly trying to present.

There seems to be a tendency among some reviewers to criticize movies for what they’re not—especially those innovative or idiosyncratic documentaries that don’t look like TV documentaries. IndieWire’s savage “D”-grade review of Eno seemed particularly harsh. I actually shared some similar concerns about the documentary in my own evaluation, but the reviewer was so dismissive of the director’s “generative documentary” experiment that they refused to see any value in the film whatsoever.

On the flipside, I have been shocked by the near unanimous praise for Skywalkers: A Love Story, perhaps the shallowest and most audience-pandering example of danger porn I’ve ever seen—it’s got nothing on last year’s The Deepest Breath. About two Russian young people who climb atop skyscrapers and post videos of themselves risking their lives to earn money and followers and their evolving romantic relationship, the documentary offers an Instagramable level of understanding of the social, economic, and political forces that are sending dozens of young Russian people to plunge to their deaths for your viewing pleasure. Here I go, criticizing a movie for what it is not. But in the case of Skywalkers, you’d think reviewers might at least mention this fact, or that the two young Russian protagonists are risking their lives for pretty photos, while tens of thousands of their fellow young citizens are dying in Putin’s meat-grinders in Ukraine every day. The film mentions Russia’s destruction in Ukraine for about 10 seconds. This isn’t reality; this is a Reality TV show, and most of the reviews seemed to be so enamored of its daredevil entertainment value they completely missed its irresponsible shortcomings and omissions.

This morning, I read that Rooftop Films programmer Dan Nuxoll had the same concerns as me. “I honestly can't believe how many terrible takes there are this year at Sundance,” he wrote in a highly read Facebook post. “True dark ages in film criticism. Some of the worst films I have ever seen at Sundance being praised, while truly authentic and emotional gems getting panned for not being more obvious and literal. Worse than ever, and deeply, deeply anti-intellectual and anti-art. If you want things explained to you that's what Wikipedia is for.”

Really great piece

Thank you! Excellent article.