McFilm Festivals: How "Chain" Festivals Can Be a "Lose-Lose" for Local Film Communities

From Sundance CDMX to Tribeca Festival Lisboa, Beware the Film Festival Franchises

Over the last few months, two news items have conspicuously come across my feeds: The struggles and shuttering of film festivals (the end of the Human Rights Watch Film Festival; Hot Docs’ troubles; the challenges at Sundance) and the rise of major festivals announcing satellite events (Sundance Film Festival CDMX; Tribeca Festival Lisboa; Sundance Film Festival Asia; Sundance Institute x Chicago). Hmm, could these be related?

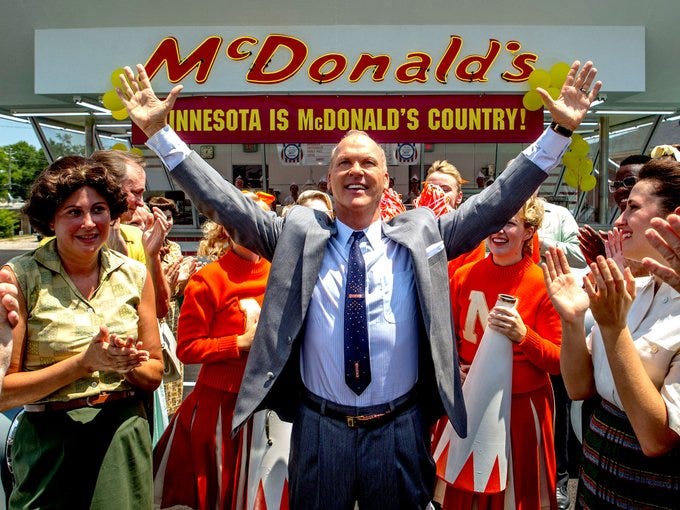

I don’t have any insider knowledge of the economics of such events, but it would seem that in an environment where festivals are seeing “declining revenues,” these franchising opportunities are a way to make money, consolidate their power, and expand their brands during these trying economic times for indie film. Like a chain store, these franchisees presumably get to operate for a fee; and in doing so, they get to use the established brand of the franchiser to promote their own event and seemingly cash in on attendee sales or other revenue streams. (Or as McDonald’s’ website puts it: “As a Franchisee, you have the independence of running your own business backed by the training, guidance, and support of the McDonald’s system.”)

I expect this is not what Dear Producer had in mind when they published their call for “Sundance Reinvented” a few months back — for the festival to move out of Park City and “transform itself into a year-round, multi-city roadshow catered to audiences.” This would expand access, they argued, and cut costs for filmmakers to attend pricey Park City. But local film festivals and art-house theater owners in regional markets did not like the idea.

As former New York Film Festival Senior Publicist John Wildman wrote on my Facebook post about the “Sundance Reinvented” proposition: “Nope. Sundance can figure its own shit out. Leave Tallgrass, Heartland, Naples, Indie Memphis, Cleveland, Bend, Oxford, Dances With Films, Bentonville, Julian Dubuque, Cucalorus, Sidewalk, San Luis Obispo, and so many other regional fests that have been key stops on the tour to discover, debut, and actually support independent film and filmmakers alone to keep that vital ecosystem alive.”

Wildman has a good point. What is the impact of Sundance CDMX on the many longstanding film festivals that already exist in Mexico City? Lisbon already has some terrific festivals devoted to independent film, IndieLisboa and DocLisboa—what is Tribeca’s impact on these events, particularly DocLisboa which takes place over the exact same dates as Tribeca’s new event this October in Portugal? (At least they could have picked a different month!)

In Chicago, some stakeholders are heralding the arrival of another Sundance export, “Sundance Institute x Chicago,” as a validation of the local industry’s growth and a means to contribute to it. See this Chicago Tribune Op-Ed by former Chicago Film Office chief Rich Moskal, who argues, “Big brands get attention. They’re built for it. And make no mistake, Sundance is big. It expects, of course, that its enduring spotlight will accompany it here to Chicago. And … there are legit expectations for collateral benefits to be realized across the local festival, art house and filmmaker ecosystem.”

But big brands are not necessarily good for the local community either. As Naomi Klein argues in “No Logo,” “Branding is, as its core, a deeply competitive undertaking in which brands are up against not only their immediate rivals (Nike vs. Reebok, Coke vs. Pepsi, McDonald’s vs. Burger King, for example), but all other brands in the mediascape.”

To that point, Sundance’s “big brand” has the ability to threaten the existing festival landscape in Chicago. As someone who works for both the Chicago International Film Festival and Chicago’s Doc10 film festival, the latter of which has a lot of Sundance documentaries and has built its reputation showcasing the best docs to come out of Sundance, it’s no surprise that I might feel threatened by the endeavor. What if large festivals like Sundance and Tribeca became even more proprietary about the films they screen? In a time of competing resources and dwindling revenue, they certainly could. And if they did, they could kill Doc10, and probably a lot of other regional spring festivals, if they chose to hold back their best films for their own events in those markets.

For smaller festivals and indie theaters, which often have close ties to their local communities, the arrival of well-branded McFestivals in their backyards could also backfire generally by removing the intimacy, authenticity, and community of these more homegrown film festival experiences in favor of something “splashier.”

As Klein writes about the corporate sponsorship of events, “Too often, however, the expansive nature of the branding process ends up causing the event to be usurped, creating the quintessential lose-lose situation. Not only do fans begin to feel a sense of alienation from (if not outright resentment toward) once-cherished cultural events, but the sponsors lose what they need most: a feeling of authenticity with which to associate their brands.”

With Sundance and Tribeca taking themselves on the road, perhaps it’s even their own brands that will be strained and damaged in the long run. While these expansions might look good to board members or corporate investors (Tribeca is a for-profit, remember), it may not look good to indie filmmakers either, who could end up being merely the product these festivals and their franchises are selling.

The lack of collaboration from Sundance with other events already planned in Chicago is galling.

“May one’s success not limit the opportunity of any other.” Wouldn’t it be awesome if all festivals adopted this as one of their First Principles? And then made all totally accessible. It would be a start of a Code Of Collaboration. And then from there…